Hans Coper, Theory and Object Analysis.

Crafts Study Centre, Farnham.

MA Interior Design

2014.

Things made of light and dark. Hans Coper : Brian Clarke. Sainsbury Centre, Norwich UK

A vessel (as membrane/threshold that can hold social rituals/traditions and memories) seems to occupy space but simultaneously be occupied by space.

Theories of relativity and uncertainty have shown that all matter, even the airy oxygenated void inside a vessel is energy, and that it is composed of the same building blocks generated from exploded stars. (Daintry2007:10)

Water, although fluid it is supremely germinative and represents the condition of all potentials.(Eliade Mircea l983)

Permeable in flux, water and water’s symbolism became the pagan’s way of intuitively knowing the world. Matter was plastic, fluid and changeable. The body was plastic with parameters defined not only by individual consciousness, but also in relation to other realms of the physical world.

The pagan participated in a vast mythology where his identity changed according to narrative fantasies that combined and recombined human and animal activity endlessly, weaving together memory, reason and sensation. In this permeable world there is no sharp division between things or between life and death. It is a world of energetic flow where bodies can indifferently become attached or unattached from myriad objects and forms. (Daintry2007:9)

Flexible Ways of Seeing/Re-Making the World.

“A large part of the reason for making is to see things that I have never seen before, to build something which I cannot fully understand or explain.”

Artist Statement, Ken Eastman.

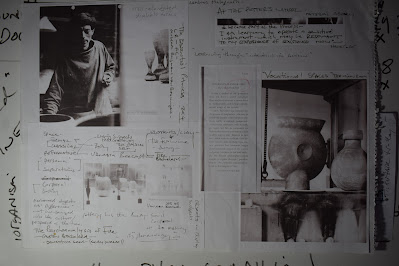

Drawings in the form of tracings were gathered from the flat planes of the display cabinet; these were further superimposed in an attempt to map the surface and forms of the Hans Coper pots and to explore their volumes and interior spaces. These new sight lines subjectively link surface details with profiles into the possibility of new spatial forms. These plans and mappings became the starting point for a series of slab and thrown assemblages. Thrown and slab worked clay forms in T Material, preliminary drawings done in-situ some with annotations. (Russell Moreton. 2014)

Rotterdam Exhibition with Lucie Rie. 1967 Hans Coper.

His arrangement was highly original and innovative, he showed his families of vases in groups, emphasising their subtle differences in form and surface treatment. The space between the pieces was just as important as the objects themselves. The architectonic character of Coper’s pots become visible through their dry, stone like skin and the sophisticated way in which Jane Gate photographs the work.

“Potters of reconciliation, they sought a marriage of function and beauty.” Douglas Hill SF author/intro to exhibition.

Craft Study Centre Publication 2014

Object Analysis

Name of object: Vase, flattened oval form on a cylindrical stem, pinkish cream to grey glaze over manganese on exterior, manganese over interior and recessed foot. It is decorated with incised lines on back and around the stem with concentric rings incised on the foot

Accession number: P.74.28

Maker: Hans Coper

Construction techniques:

Materials: stoneware

Dimensions: 22.2 x 18.8 centimetres

Date made: 1960s

Provenance: Made in Hammersmith, London. UK

Given to Muriel Rose by Hans Coper in 1966

This thistle-shaped vase is constructed from five individually thrown pieces. The joints making up the pot have been selectively accentuated with the residues of the manganese engobe. Incised geometric marks remain from the initial turning process of the component parts, prior to the construction of the pot. (Russell Moreton. 2014)

Name of object: Vase, unglazed rim. manganese interior, decorated with vertical scoring on the exterior

Accession number: P.74.103

Maker: Hans Coper

Materials: stoneware

Dimensions: 12.7 centimetres

Date made: 1950s

Provenance: London. UK

Single thrown form with the remains of the sgraffito technique after the ceramic has been heavily abraded after firing. The vertical lines of the sgraffito technique and the form itself are similar to Lucie Rie's flower vases, see Lucie Rie by Tony Berks page 112.

This single thrown form perhaps best illustrates the creative union of both Coper's and Rie's practices, the form almost a kind of beaker might itself been inspired by the "dark pots” Lucie Rie found whilst visiting Avebury Museum. (Russell Moreton. 2014)

Name of object: Squeezed ovoid-shape vase with flower holder inside, manganese interior

Accession number: P.74.30

Maker: Hans Coper

Materials: stoneware

Dimensions: 22 x 22 centimetres

Date made: 1970s

Provenance: London. UK

Wheel thrown forms, comprising of bowl, open cylinder and an interior ring acting as a flower holder. The bowl form has been turned before being jointed with the upper section. The piece was then indented at four points to form an ovoid form. Pronounced incised horizontal marks remain from the joining, which has been further transposed by the action of becoming ovoid. Very subtle and restrained use of the manganese engobe followed by Coper's characteristic post firing technique of abrading the surface of the ceramic. (Russell Moreton. 2014)

Hans Coper : Working Notes CSC/10 March 2014.

Notes re/statements

1. Specific to the form in question.

2. Context in relation other similar forms.

3. Key Words: Impregnated, Incised, Eroded, Reduction, Surface, Soil, Abraded Surfaces, Machining, Grinding, Assemblage, Components, Parts, Groups, “Aryballos,Spade, Thistle, Diabolo, Cycladic, Spherical,” Sculptural, Pottery, Architectonic, Space between Forms, Spatial, Sensuality, Form and Fold, Bodily Spaces, Light and Dark, Clay, Water, Fire, Agency, Difference,

Extracts from catalogue “The Essential Potness, Hans Coper and Lucie Rie 2014”

“I become part of the process, I am learning to operate a sensitive instrument which

may be resonant to my experience of existence now.”

“My concern is with extracting essence rather than with the experiment and exploration. The wheel imposes its economy, dictates limits, and provides momentum and continuity. Concentrating on continuous variations of simple themes I become part of the process.”

Artist Statement, Victoria and Albert Museum/Collingwood, Coper Exhibition 1969. Small Beige Spade 1966.

The body comprises a thrown circular form, from which the bottom has been flattened into an oval and the lower section has been pressed together.

Throwing rings are visible on the inside.

Areas of the white engobe have loosened from the underlying layer during firing and formed blisters.

Cycladic Vase 1973.

Blisters in the slip have been sanded down to reveal a rust coloured underlying layer. Medium Sized Spade 1973.

There is a clear delineation between the light upper section and the rougher and darker lower section.

Small Thistle Shaped Vase 1973.

There is a large incised circle on one side of the disc and a smaller circle on the other. Hans Coper’s characteristic use of light engobe and dark manganese oxide has produced a hazy texture.

Black Aryballos 1966.

This ceramic form has its origins with the Oil Flask used by athletes in Greece and Asia Minor.

Tall elongated diabolo forms.

After being thrown the cup has been formed into an oval and then indented at four points.

Text Fragments. Momentum Wheel.

It is difficult to determine in which order the parts were assembled.

The underlying surface is showing through the grooves that are linking the body and the base.

The manganese engobe is demarcating dark and light zones through an undulating incised line.

“Rings” caused by the placement of a prop in the kiln. Brown-Beige Colorations.

Sensations caught within the form.

Soil like deposits/remains.

Reductions of the fired surface.

Abraded Surfaces

Incised Line.

Droplet.

Blisters, pricked open and sanded after firing. This process has produced an irregular, patch surface.

Parallel lines have been incised with a pointed object on the exterior of the base. Thistle Shaped Vase 1966.

The dark brown patches (around the jointing of the pot) and flecks appear randomly distributed but have been purposefully placed to accentuate the structure of the vase. This flat vase with the contour of a stylised thistle flower is made up of five individually thrown pieces. The tall cylindrical foot supports a vertical disc, comprising of two individually thrown flat plates. It is as though the disc has sunk approximately ten centimeters into the foot.

Spherical Vase with Tall Broad Oval Neck 1966.

The transition from sphere to neck is accentuated with darker colourations.

Hans Coper

Hans Coper's iconic assembled ceramics frame the later part of the twentieth century with an ambivalence of both alienation and reconciliation. His pots reveal differences that have resisted the homogenizing effects of the culture of the time. They embody and are a physical testament to what the potter himself has reflected on his life, "endure your own destiny"1 2 within the space and time of the human condition.

Bom in 1920 into a prosperous middle dass background, his childhood years were spent in the small town of Reichenbach in Germany. In 1935 his father Julius, is singled out like many other Jewish businessmen for harassment and ridicule

under National Socialist Party. This would result in the Coper family moving frequently to escape the attention of the Nazis. Tragically in 1936 Julius takes his own life in an attempt to safeguard the future of his family. The remaining family. Erna Coper and her two sons return to Dresden. In 1939 Hans at the age of 18 leaves Germany for England, the following year he is arrested in London and interned as an enemy alien. He spends the next three years first in Canada then returns to England by volunteering to enroll in the Pioneer Corps. In 1946 a meeting with William Ohly who ran an art gallery near to Berkeley Square, brought about an opportunity for a job in a small workshop run by Lucie Rie, a refugee potter from Vienna. Hans Coper now began earnestly through his engagement with ceramics to reveal a continental modernity "whose work seemed uncomfortably abrasive to the traditionalists."*

Hans Coper and Lucie Rie worked together at Albion Mews for 13 years forming a friendship and a working relationship that was mutually reciprocated through practical concerns, innovation and experimentation. There is a creative synergy in place through their mutual sharing of process and experimentation within the practicalities of the studio space. A documented instance of this reciprocal inventiveness is in the appropriation of the technique of "Sgraffito" which Lucie Rie employs after being inspired by some Bronze Age pottery at Avebury Museum bearing incised patterns, which are displayed with some bird bones, which may have been used as tools to incise the pottery. These "dark bowls of Avebury"3 are transposed through the use of manganese engobe and a steel needle into Lucie Rie's ceramics, Hans Coper although not present appropriates the bird bone for the engineered steel of a pointed needle file and uses the action of an abrasive hand tool to remove layers of the manganese engobe. In this way Coper is enacting onto the surfaces of his ceramics, the very agencies that Modernism was acting out in the realms of architectural space and surface treatment of materials. In 1959 a move to Digwell Arts Trust would bring to a close his working relationship with Lucie Rie. Coper now became involved with a number of architecturally based projects through the Digswell Group of architects and building professionals. Coper's engagement with the Digwell Group was not without problems and creative frustrations, but seen in retrospect it became an experimental period where Coper was strengthening his ability to bring his pottery into a spatial communion with the modernist architectural sensibilities of the time. However it was a wartime friend Howard Mason who introduced Coper's work to Basil Spence, from this introduction Hans Coper was commissioned to design the candlesticks for the new modernist cathedral at Coventry. The Six Coventry Candlesticks completed in 1962 explicitly reveal a sensitive and progressive spatial awareness to the architectonics of built spaces. The candlesticks delicately tapered and waisted are made in sections and assembled on site onto rods set into the architectural interior. These assembled thrown and fired towering forms seem to be more about a presence than their actual physicality. They appear to paradoxically transcend the monumentality of their setting through their very immateriality, their slight of form being perfectly balanced to accommodate a single candle and its temporal flame.

As a maker of pots he was in constant touch with his working process, an analogue process, a creative membrane that surrounded the agency of making and thinking. He was able to pursue his vocation "My concern is with extracting essence rather than with the experiment and exploration"4 His resultant works reflect what might be termed a "machining in" of a creative durability that is both ancient and modern that contains both tensions and fragility, and that above all seems to exist in a state of timelessness.

His assembled "pots" are constructed from thrown components, "throwing" as o process that he remarks on "I become part of the process. I am learning to operate a sensitive instrument, which may be resonant to my experience of existence now". It is through the wheel, the body and the interplay between clay and air that the inner space that defines the form is created. Adam Gopnik writing about the art of Edmund de Waal describes what I might be termed a spatial sensibility "the pot-ancient as it is. is the first instance of pure innerness, of something made from the inside out."5 Hans Coper further adds sensuality to this "innerness" when he encloses it in a skin that appears archaic through a deeply physical surface treatment of engobes, incised grooves and scratching of the raw pot; then when finally once fired the dry vitreous surface is further machined and abraded to give a graphite-like sheen.

Hans Coper's pots speak in silence of this interior "architectonic" space that is itself reverberated through an almost archaic modernity. He seems to be able to tune the interior, to load its mass, its void.

There is a strong sense of the vessel, the concrete with the emptiness, even an analogy to corporality set in motion by his treatment of the surface and interiors of his pots. The pots themselves belong to ever extended families, to new familiarities created by the subtle interlays between the negative spaces created through the spatial awareness that has been crafted into their very making. The pots through proximity with each other are in a spatial communion, they act to define particular spaces by defining boundaries and creating thresholds between exterior surfaces and space. These pots are themselves are 'encounters' they ask us to be attentive to the responsive sensory inner space set up in residence by the permeable world of the ceramic vessel.

1 Birks. Tony. 1983. Hons Coper. London. William Collins Publishers. p75.

2 Birks, Tony. 1983. Hans Coper. London. William Collins Publishers p22.

3 Birks. Tony. 2009. Lucie Rie. Catrine. Stenlake Publishing ltd: p44.

4 The Essential Potness. Hans Coper and Lucie Rie 2014. Collingwood and Coper Exhibition 1969. Victoria and Albert Museum.

5 Gopnic.Adam 2013. The Great Glass Case of Beautiful Things : About the Art of Edmund de Waal. New York; Gagosian Gallery: p6-7

.jpg)

.jpg)